Category: News

What really causes Addiction?

A talk by Johann Hari suggests that everything you think you know about addiction is wrong. As he has watched loved ones struggle to manage their addictions, he started to wonder why we treat addicts the way we do — and if there might be a better way.

The opposite of Addiction is not abstinence or sobriety. The opposite of Addiction is CONNECTION. In SCA we connect to others that share our addiction. We connect to a fellowship that supports us and we can connect to a Higher Power, a spirituality that unconditionally loves and guides us.

Could addiction be about isolation and being disconnected from society? Listen to this TED talk by Johann Hari for some interesting insights on this subject. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PY9DcIMGxMs

Questions & Thoughts

“I am hopping and trying to find meetings with open communication. This will only help me with my own Honesty, Shame, Trust, Hope, Strength & Willingness to Learns and to Stay & Remain OPEN Always .. Please 🙏 Any HELP IS & Will be Appreciated” – D.W.

Dear D.W.,

All SCA meetings support member’s sharing their feelings, experience, strength and hope with each other, that they may solve their common problem and help others to recover from sexual compulsion. If our behavior was illegal, we might seek out someone (like our sponsor) with whom we can be entirely honest without fear of consequences and choose to share our feelings at meetings instead of the details. We ask members to respect the anonymity and confidentiality of every person we meet and everything we hear at meetings.

Anonymity assures that our meetings are safe for those in pain. This respect of anonymity keeps the program safe for members and prospective members to attend. Through the anonymity offered at meetings, we find a refuge where we are neither judged nor shamed. Many of our meeting’s format have a sharing portion where members may share breakthroughs or breakdowns in their program, ask questions, get current on situations in their lives, or just express honest feelings they may be in touch with. Crosstalk is discouraged and is defined as: Giving advice, criticizing, or making comments about someone else’s share, questioning or interrupting the person speaking, talking while someone is sharing, or speaking directly to another person rather than to the group.

We suggest attending a few meeting to find a “home” meeting that you feel most comfortable. We have available in-person, on line, virtual and hybrid meetings that can be found on our website: sca-recovery.org

Please make these announcements at your meetings, intergroup and to other interested parties

Sexual Addiction or Sexual Compulsivity: What to Call It?

Should sexually compulsive behavior be designated a disorder or an addiction? Relatively recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) added compulsive sexual behavior disorder (CSBD) as an official diagnosis. Clinicians have long required clear criteria to establish a diagnosis and engage in a treatment protocol.

For additional information read the article from Psychology Today: https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/love-and-sex-in-the-digital-age/202411/sexual-addiction-or-sexual-compulsivity-what-to-call-it

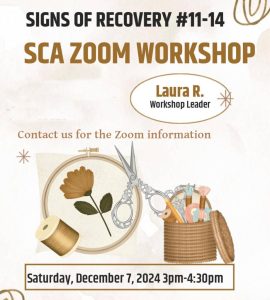

Workshop on the Signs of Recovery

ENTRAPPED-A SEXUAL HISTORY

My first sexual experience was at the age of eight when my neighbor across the street molested me and forced me into orally copulating him. That afternoon was the start of the worst year of my life, until this year. Thanksgiving morning my grandfather woke up sick with what we all thought was either the stomach flu or food poisoning. By Easter he was being treated for bile duct cancer. He passed away several months later in July. My grandfather was my male role model and the first person who I was close to that died. The entire time he was sick I would still on occasion be molested by my neighbor, which also eventually progressed into him sodomizing me as well. A couple of months after my grandfather died as I entered the 4th grade, I had an extremely authoritative and emotionally abusive teacher. With the emotional loss of my grandfather as well as the sexual abuse at the hands of my neighbor I began having disciplinary issues at school which only led to me having more troubles at home.

Things managed to settle down and the abuse from my neighbor stopped, however when I started middle school I was attacked in the boy’s locker room by two older boys. That incident was the first time that I had an orgasm. Not having any idea of what had happened I was left utterly confused by the feelings they had given me and even though I was terrified by what they had done, on some level I wanted it to happen again. I began puberty around this time and became one of the tallest kids in school. This helped me make it through the rest of my schooling without any real incidents and as a good student.

Things were different around home. Most of the kids around my age also had younger siblings. As I turned 15 my erotic thoughts and feelings started to change and often centered on doing things with the younger boys who lived on our street. I was pretty sure that I was gay. I had also been raised in a Catholic household and firmly believed that it was a mortal sin to be a homosexual. I was terrified of my parents and classmates finding out. Feeling like I had no one to talk to that would understand, I escaped by spending hours looking at pictures of boys between the ages of 8-14 on the internet. That would eventually lead me down the road to the outer periphery of the dark web and chat boards. Being in denial of the dangers of what I was doing I would openly confess on those boards to being 15 years old and sexually attracted to my younger neighbors. In the beginning I was seeing validation and support about my feelings and my sexuality. Those sites also hosted child erotic images and soft-core pornography of young boys fully nude. Eventually, I’d make the mistake of asking older members for pictures from their private collections involving child pornography. These images “triggered” old feelings and intensified my sexual obsessing.

At 17 I was able to drive myself to school and back home and depending on traffic resulted in me getting home from school about 20-30 minutes before everyone. That would regularly be time for me to masturbate to whatever hot guy I saw in the locker room or look at pictures from that site of younger boys. One afternoon when I was alone in the house masturbating to nude boys on the family computer, I left the room and my mom and sister came home and saw them. I was forced to come out to my mom although I tried to say that I wasn’t really gay, just confused. My mom decided to get me into therapy to change my behavior. That attempt would last barely a month until I swore to my mom that I had learned my lesson and would never do that stuff again.

That was a lie and the first of what became the pattern of lying that I would need to do in order to cover up my compulsive sexual behavior. However, my behavior would only get worse and things more unmanageable. Now in college I had classes free on Friday which meant I had the entire day, from the time I woke up to the time my sister got home from school, to look at child erotica and masturbate. It was also around this time that I started posting ads on-line for casual hookups. I had my first consensual sexual experience with another man, but it only brought back painful memories and flashbacks to the molestations I had gone through as a kid. This led to several attempts to work on my “issues”. After several months and several therapists I realized that I was still not fully ready to come out of the closet and admit to being gay. One positive did happen, it helped me to finally realized that I was going down a path that could lead me to getting arrested. That helped to get me to stop looking at images of child erotica, but I still would regularly post ads looking for guys to have sex with. Slowly this started consuming more and more time cruising until I met a guy that I could hook up with “regularly”. The only problem was that he was 17 and I was 20. Eventually, he would move away to go to school ending what “relationship” we had.

During my final year in college a fellow student called the campus police after finding my lost thumb drive containing pictures of underage boys that I had saved from the internet over the years. I was charged with possession of child pornography. I accepted a plea agreement to a lesser misdemeanor charge and sentenced to 3 years of formal probation. After twice violating my probation I was then sentenced and served 40 days in county jail. The one positive thing that came out of this was that I found a sex addiction therapist who I still see to this day.

For the next several years I continued looking for hookups and was not always careful about checking how old they were. I now had stable full-time employment, which meant that I could afford hustlers and prostitutes.While I was able to be financially responsible for a lot of things, any “extra money” was spent on obtaining sex. This became more problematic over time. In 2016, I started working for families with kids who had developmental delays. I found myself attracted to and fantasizing about one the children that I was assigned to. I knew that I could never do anything sexual with him, so I found some regular sexual partners that I paid to roleplay and act out some of my fantasies. I was now spending more and more time cruising on hookup apps and trying to set up the perfect erotic encounters. I found that I was less able to manage all the details involved. Later that year I was terminated for leaving inappropriate materials at the job. I decided to change my career path and go back to school to work in the medical field. Since I hadn’t really saved any money I moved back home and became completely dependent on my parents. This additional stress only made me find new ways of acting out. As my addictive activities became more risky and dangerous the more I needed to escape. Eventually, I was able to get a job at a Covid testing site. The long hours at work helped to build back my bank account that I had completely depleted.

Eventually one of my hook ups turned into something more, for lack of a better term it became a sugar-daddy relationship. He knew how to manipulate my self esteem. It wasn’t long before I developed some very serious feelings for this boy and became willing to do anything he wanted me to do. We carried on this pay-for-love relationship for roughly a year. It was hard to remain in denial as I would drive him around to meet with drug dealers so he could get his fix and then ignore me while he got high enough to be willing to do stuff sexually. I guess that’s what Love Addiction is, continuing to stay with a person in spite of all the red flags. Even with all that I continued to stay with him. Our relationship only ended when he eventually blocked me on all his social media accounts. I no longer had a way of communicating with him.

This became a bottomless spiral that would lead me to my rock bottom. Work became my distraction from the pain and shame that I was feeling. I didn’t want to be around any of my family or friends, so I became more and more isolated. This isolation only fueled my addiction for underage boys. I escaped into the internet world of pedophiles. Eventually my “ex” would reach out to me and created yet another story, another reason for me to give him money. When that didn’t work, he resorted to blackmail, saying that he was really 16 when we met and the pictures I had of him would be considered as child porn. I called his bluff. Several months later I was arrested at my parent’s house for possession of child porn and Distribution of Obscene Matter to a person under the age of 18.

The stress of the child porn case carried over to my job and I was asked to take a paid leave of absence. I felt like I was having a mental breakdown. Even the pending court case did not stop me from needing to act out. I contacted someone who’s profile said that they were 18, but relatively quickly into the conversation he told me me that he was really 14. That’s when I entered the addiction bubble and turned the conversation to sex. We agreed to meet later that night. In reality there was never a 14-year-old boy, and I stepped right into a sting operation set up by some online vigilantes with a film crew. Eventually, they would call the police, and I would be arrested again. I’d spend the next 5 days in custody before being ROR’ed by the judge. Four months later we reached a plea agreement with the District Attorney’s office, and I accepted a plea to a lesser charge and agreed to attend SCA meetings.

So, what have I managed to get out of this SCA 12 Step program since I’ve been attending? Mainly it’s helped to break down all the isolation that had become such a big part of my life. It’s also to some degree helped me see that I am not alone in my struggles with sex and love addiction. I’ve become more aware of how denial and minimizing is a big part of this disease. I have found a sponsor and started to work the first few steps of this program. It has also helped me become more aware of things that I hadn’t realized had as much of an effect on me and those are things that I now know I need to address in my therapy. The program has also shown me just how powerless and unmanageable I let my life get. Working with my sponsor has given me an appropriate outlet where I can talk and discuss the things that may not be safe to be brought up in therapy. He’s also given me someone who I can check in with rather than immediately act-out over. But most of all it has shown me just how compulsive my behavior was and is, and if I use the tools of this program I will manage to successfully redirect myself, one day at a time.

Serenity By The Sea Oct. 23rd-26th

SCA ISO/NYC will present a “Welcome to SCA” workshop at the Provincetown AA Roundup. The 2024 Roundup, is celebrating its 37th year of recovery, unity, & service for the LGBTQ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans-gender, Queer, Questioning) community and all of their friends. Our workshop will be on Saturday, Oct. 26th at 10:30 am. This well-attended AA event, has also invited other 12-Step Fellowships to present workshops this year.Here is the link to register for the P-town Roundup: https://www.provincetownroundup.org/index.aspx

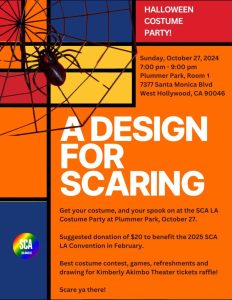

SCA L.A. Costume Party

Awareness set me free: A Prisoner’s Story.

I attended my first Twelve-step meeting for sex addicts a decade before I was arrested and given a life sentence. My attendance at that meeting was a legitimate demand from my second wife. But I was in full-blown denial then and didn’t see it that way. I thought I was in control and adequately managing my life, but I wasn’t. The feeling of hopelessness that began in childhood took half a lifetime for me to finally hit rock bottom before I eventually realized I needed to leave sexual compulsivity behind me. Becoming aware that my past compulsive behavior does not totally define me has been an early step on my path of recovery.

I was born into a traditionalist, conservative, fundamentalist Christian home to parents who had the best intentions but who believed in authoritarian parenting. Mom was raised in an abusive and alcoholic home. My parents grew up in the 1950s and intended to bring up their children as they were raised. They used fear to obtain obedience from my sister and me and were resistant to the rapid social changes of that era while firmly believing that they would prosper with God behind the wheel.

My parents were inspired by the “fire and brimstone” sermons we heard every Sunday morning and strove to be people-pleasingly friendly at church but would yell at each other during the car trip home. Before age five, I learned from the church and my parents that there was this thing called sex, and it was sinful. That learning left me incredibly curious about sex.

It wasn’t long afterward that I had trapped two female play dates in my bedroom, unsupervised, where I suggested we play made-up games centered around their bodies. I once stole another girl’s clothes after a pool party, leaving her to run naked through the house. I was excited to challenge the secretive taboo that was so sinful, yet no one wanted to talk about it. But I also felt shame for sinning and for embarrassing my parents. I would silently ask God’s forgiveness as I had been taught, only to keep repeating the cycle.

Also, at age five, my father began spanking me with a belt or paddle to punish what he believed were my misbehaviors, even on the first offense. When our mother got angry, she yelled at us kids. However, when Dad got angry, his discipline increased in the level of violence. The first time he physically abused me this way was when I cut my little sister’s hair one week before Easter. My sister and I had become close. At times, she seemed my only friend as we were largely isolated from the outside world. Although neighbors and others saw our parents as loving and caring, our home could be unpredictable and chaotic, and our parents’ love was often conditional. Growing up feeling unworthy and resentful, I self-isolated and missed out on a healthy social environment.

At age seven, Mom fell ill with an autoimmune disease that tested the family’s faith in God and had a harmful effect on us kids. My parents doubled down on their faith in the shadow of Mom’s chronic and terminal illness. I struggled to make sense of the abandonment and came to resent and question God while also coming to understand the arbitrariness of my parents’ beliefs and behaviors. I became depressed. Unsupervised, with Mom in bed or in the hospital nearly all the time, and Dad, a workaholic, I played “doctor” with my sister several times. I spied on her and her friends in the shower through the window and a hole in the ceiling.

I was 11 when I discovered masturbation. In middle school, I felt pressure to have a girlfriend, yet I believed myself socially inept. But I learned I could have any girl I wanted if I fantasized about her while masturbating. This quickly became my escape from all the pain I was experiencing in the real world. I was already using sex to escape fear, depression, helplessness, rejection, and loneliness but also to feel powerful and in control. Sexual fantasy plus masturbation became my usual remedy and remained so for nearly four decades.

My life had become unmanageable by age 13. Mom’s illnesses had progressed to the point where she was partially deaf. One night, trapped in a hot and stuffy RV during a three-week, multi-state family vacation, the television volume was super loud so that Mom could hear it, but I could not sleep. With the heat, noise, resentment at my parents, and feelings of being helpless and unworthy because of their rules and Mom’s illness, I snapped. Hidden from their view by only a privacy curtain, I sexually assaulted my sister to find relief. I also found regret and shame. I hadn’t yet learned remorse.

My sister kept this secret for five years, also from shame, until she had a nervous breakdown. My parents had me take an anger management class. Still a teen, I didn’t want to be there, and I experienced little change in my negative feelings and outlook. This family secret continued until it surfaced in my arrest proceedings decades later, re-traumatizing my sister.

My sexual compulsion got progressively worse over the next three decades. I committed date rapes by forcing girlfriends to go farther than they wanted to, and after college, I sometimes sexually harassed women. After college, fighting loneliness, I met my first wife through a dating service, trying to earn my father’s approval. Within the first year of marriage, I sexually assaulted her, cheated on her, and then divorced her to begin a short-lived relationship with a re-discovered high school sweetheart I had found online.

On the rebound from those two women, I eventually married another woman whom I had met at work. My second wife and I had an active, enjoyable, creative, and communicative sex life, but that is where the intimacy started and ended. For my part, I was challenged to distinguish intimacy from sex. Meanwhile, my sexual compulsion progressed further with my second wife over the next 20 years until my arrest.

Internet pornography became a major acting out behavior. I came to believe daily masturbation was medicinal, even as I could already sense it was interfering with trust and intimacy in our marriage. Even so, the internet allowed me to easily seek out prostitutes, and gradually, my target age lowered from 20-somethings to teens. I still spied on showering family members and even helped my wife’s friend buy drugs in exchange for sexual favors.

At age 42, my wife and I became foster parents to my wife’s niece and nephew, and three years later, the county formalized the adoption. I was so busy now I had no time for prostitutes anymore, to whom I’d paid thousands of dollars. Our family finances were pitiful, and we were living paycheck to paycheck. We fought incessantly. I had been cheating on her for decades, only rarely getting caught, a deceptive manipulator because of my growing list of compulsions in the face of all the new stresses piling on top of the old stress: sex, coffee, sweets, and work.

I arrogantly believed I was entitled to my “righteous” behavior. My wife and I were not on the same page. I now recognize our behavior before the kids to be emotional abuse, a form of domestic violence. At the same time, I still felt unworthy and increasingly helpless. My wife grew up in a far more physically and emotionally abusive home than I, and she began to show her contempt and criticism towards me, trying to restore control over our endlessly challenged lives. I gave up. I could no longer see any future. I didn’t see suicide as an option, but “social suicide” was on the table. I was beyond depressed and felt cornered.

At age 46, I turned my sexual compulsion on my eight-year-old adopted daughter, a horribly heinous crime that robbed her of her innocence and destroyed whatever future she might have had. I was motivated in part by my then favorite porn video, which involved the portrayal of a girl about the same age as my daughter–the age my sister had been when we played doctor. Just as I was a target of my wife’s wrath, so my daughter seemed to me. Promising her protection, I groomed her into performing sex acts with me. I justified the acting out by telling myself no one—neither God nor society– could understand the unique bond we were developing.

I had become delusional, believing we were having an affair and that I was causing no harm. My beliefs reflected messages I had learned in childhood, as I interpreted them from my parents, middle school peers, and the media. Things like: “Men take what they want,” It’s ok if no one finds out,” “A child’s voice doesn’t count,” and, finally, “My daughter consents because she’s going along with it.” I thought I had shed most of these beliefs but surprisingly learned that I had actually held onto them. Yet, I was still in denial. I told myself my daughter and I were equals. I was completely oblivious to how much power I had over her as her father– a power I selfishly and recklessly abused. I told myself that each time I sexually abused her would be the last time. The shame was strong, but the compulsion was stronger.

One day, I got careless, and we were caught in the act. For a few months, the year-long sexual abuse that I had committed against my daughter had become another family secret until an anonymous tip led to my arrest. I hit rock bottom in jail. Divorce. Loss of parental rights. Loss of everything. Shame. Depression. Thoughts of suicide.

Six months later, I experienced the turning point that began my path to recovery as I wrote a letter to my father about how to best care for my daughter in the aftermath of my crime. I had begun to realize that the best thing I could do for my kids was fix my problems and become the best person I could be. I had finally moved past much of the denial and began to recognize I needed help. Once I got to prison, I found that help.

Only in prison was I able to face the truth of my sexual compulsion. I knew I needed help, but I did not know what that help looked like. I knew that my low self-esteem was behind my sexual acting out, but not why. I wasn’t super motivated because I had multiple consecutive life sentences and expected to die in prison. I found many 12-step groups and self-help correspondence courses addressing all sorts of character defects. But, as sex crimes usually rank as the lowest in a prison hierarchy where murder is still often viewed with some admiration, I feared for my safety every time it was my turn to share in those groups. Criminals and Gang Members Anonymous (CGA) felt more inviting to me than Alcoholics Anonymous because sexual dysfunction is among CGA’s listed criminal behavior domains. Fortunately, I took the initiative to meet other prisoners and found some mentors from across the criminal spectrum. Those mentors were the first reincarnation of my Higher Power and my willing introduction to 12-Step programs.

At my first AA meeting, I freely and honestly admitted I was out of control and that my life was unmanageable. I worked through the Steps, but spiritual awakening did not immediately follow. Fear of rejection or possible physical harm from gang members still made me cautious about sharing my story at meetings until I found Sex Addicts Anonymous (SAA) and later Sexual Compulsives Anonymous (SCA).

I took responsibility to work on my recovery for myself and my children’s sake. Each time I reviewed Step Four, I discovered new character defects or insights while experiencing further reductions in denial and increases in self-awareness. Listing all the times I have been selfish, resentful, dishonest, and frightened was liberating. I forgave myself; then, I forgave those I had blamed for my predicament. I learned that my beliefs shape how I respond to events and that I can learn to change my feelings about events to transform my beliefs.

Over time, I expanded my support network. I chose to be sexually abstinent, ceasing all masturbation and sexual fantasy. I worked the 12 Steps several times in AA, NA, CGA, and ACA, and then joined a fellow recovering sexual compulsive to start an SAA group in prison. When I found SCA, I knew what I wanted and needed from a 12-Step program. I discovered the SCA Blue Book to be amazingly spot-on and current with emerging medical science. I learned I might “partner” with my Higher Power, a concept not touched on in other 12-step programs’ materials.

Preparing for the parole board interview has strengthened my recovery as I learned how I came to be the person who could sexually assault his eight-year-old daughter, whom I had claimed to love and promised to protect. I studied psychology in the prison college program. I gained more insight into who I was and took responsibility for who I am, holding myself accountable for my change. My remorse matured as I recognized the ripple effect of just how deeply I hurt my sister and my daughter, my sons, my wife, my parents, and the whole community.

This awareness enabled me to make a thorough list of all those I’ve harmed across my lifespan. My circumstances won’t allow me to make direct amends for most of the harms I’ve done. Before I found a sponsor, I wrote apology letters that included blaming others. Today, I practice living amends, making thoughtful choices daily that I am proud of, and finding ways to serve others in my prison community. My daily Tenth Step is more meditation than prayer, sometimes with journaling to measure my reactions and responses to the day’s events. I look for hidden patterns of behavior I need to address, not just the sexual ones, and keep an eye open for identifying and promptly making amends when I inadvertently harm someone.

I am powerless over the impulsivity that seeks to feel good when I am stressed, afraid, hurting, angry, or otherwise struggling to get my needs met. When I nurture my support network and find joy in friends, I want more of that, and then the void is filled. But when I self-isolate, loneliness takes over. I then become a glutton for attention, affection, excitement, and sweets—chasing that dopamine rush—and the chances of acting out increase.

After five years incarcerated and three years abstinent, I still cannot fantasize sexually without drifting into thoughts about my daughter. But I can recognize when the void appears and cope in positive ways, choosing not to act out. Instead, I can replace the void with something positive, such as doing something of service for someone, especially if they don’t know I did the service. It feels great to help others when I know it will brighten their day.

About a year into my prison stay, during a study on Step Eleven, I learned to separate spirituality from religion. I had projected my father into the face of God. I gained the courage to renounce my Christian beliefs, including the existence of Heaven and Hell. This decision helped me heal from the religious abuse I’d received as a child. Within a day, I let go of decades of festering resentment against my father, God, and my second wife. Twenty years after my mother died, I let go of my resentment against her for abandoning me with her illness. I learned that personal safety means distancing myself from harm, and that includes letting go of the pain and blame from my past. These actions were instrumental in redefining God as I understood God. Now, Steps Three and Six make sense, and I can partner with my Higher Power to transform my character defects into character assets.

Today, I remain active in several groups, particularly in groups dedicated to sexual compulsion. I make weekly phone calls to my SCA sponsor. I continue to prepare myself to face a parole board 15 years from now. I’ve had some success with achieving sexual sobriety in prison. One day, my daughter and my sons may once again want me in their lives. I now value myself enough to fight for my physical and spiritual freedom because I am a human being worthy of love, including self-love. I have rediscovered the real me, the inner child who once was excited and curious about the world and confident enough to want to explore it. I have natural talents such as patience, being a good listener, hardworking, gritty, and kind– talents that once again can flourish after eliminating deception from my moral code. To these, I can now add courage, empathy, serenity, and consequential thinking.

I live an intentional, values-based, and goal-oriented lifestyle that feeds my need for dopamine and reduces impulsivity and depression at the same time. I exercise regularly and drink enough water, things I previously didn’t prioritize. I’ve stopped trying to fix others, as my perspective has broadened me to be more inclusive and appreciative of diversity of thought. I see myself as a work-in-progress.

My vision for the future is to teach health science education to adults, which may help prevent crimes and their impact on victims. I can set boundaries in interpersonal relationships, develop healthy financial habits, attend groups regularly, and continue learning. I can see when I’m deviating from God’s will in favor of my self-will and re-center myself. Presently, I practice Buddhist mindfulness meditation because the prison offers it, and it works for me.

I never expected to find the self-acceptance and internal freedom that were gifts I found in recovery, nor all the tools I now have in my toolkit to live a life not controlled by sexual compulsion. Today I facilitate 12-Step groups in prison, tutor GED and college students, and am working to build my skills as a life coach. I still make mistakes, but I remember I’ve made more forward progress than any mistakes set me back. I find gratitude every day. I’ve made things right with God, myself, and others open to my amends. I know who I am, and I’m proud of that. My past is a part of me and, as such, a thing to be accepted–not to glorify my crimes but to recognize that I survived by doing the best I could. Today, I’m happy with the knowledge that I can do better and that I am a useful member of society, incarcerated or not. I do all this with the help of God. 08/24